Camera, Lights, Action: Bringing the American Action Film

During the last decades the American action film has grown into the most profitable and widely distributed film genre. Despite its ubiquitous presence in European cinemas today, little is known about how these films were introduced into foreign film markets and with which reactions they were met. Studying the Belgian reception and circulation of these films in the genre’s formative years helps to better understand how the American action film came to be embedded in the Belgian box-office landscape.

By Lennart Soberon

Are You Not Entertained?

Spectacular gunfire, high-speed chases, and fiery explosions. The American action film is as easily recognizable as it is iconic. In the contemporary, globalized cinema landscape the action film holds power as the most profitable film genre of its time. Even in Belgium these high octane blockbusters have reigned supreme. Taking a closer look at the exhibition context and general reception of the U.S. action film in Belgium allows us to better comprehend how the genre grounded itself in Europe and with which political, economic and socio-cultural circumstances these often controversial films interacted. By studying reviews, attendance numbers and programming patterns from the late sixties until the early eighties, the action film’s inception and longer lifeline becomes apparent as something greatly entwined with wider developments within the American and West-European film landscape. As many reviews of the time discuss, the genre became something of a symbol since it greatly appealed to new audiences and modes of exhibition.

An historical evaluation of the action films helps to explain how the genre became a valuable commodity that gradually conquered the Belgian market. Moreover, an analysis of these formative years can contribute to a wider understanding of how film genres are conceived and further develop. The action film, ironically, did not enter the world with a bang as one might expect. Rather, it is the result of a slow and fluid process of film aesthetic developments, promotional framing and revisionist film historiography.

New Blood

That the existence of genres is the result of a long lasting, multi-facetted process of categorisation and revaluation, becomes clear when we take a look at how action films have been labelled in Belgium since the early years of their formation. Although film history books and genre theorists situate the first modern day action films in the late sixties, early seventies, for example Bullitt (1967), The French Connection (1971) and Dirty Harry (1972), these films were rarely recognized as such in the time.

Bullit was heralded by cultural magazine Knack in a 1984 issue as ‘the quintessential action film’, but was not described in those terms upon its initial release. While the ‘action-packed’ and ‘spectacular’ nature of the film was heavily discussed in Belgian trade press and film reviews of the time, nearly all sources place the film in the genre of the police-thriller or policier. This is not surprising since the first action films all dealt with hardboiled lawbringers that fought crime with violent measures. Despite the familiarity in setting, reviewers were also keen to point out that these films were very different from anything they’ve seen before.

While critical about the tiresome clichés of Bullitt, Belgian newspapers praised the exhilarating new form and style the film brings to the table, making it even ‘worthy to be screened in film schools’. Films such as The French Connection were even praised for their complex characters and on location shooting that brings a new degree of realism to the stale formula of cops and robbers. To Het Belang, the film is symptomatic of a new generation of ‘fierce American cinema that has (action) filming in its blood’.

Others cared less about the cultural complications and only had eyes for the never before events on the screen. Het Volk, just as most newspapers mark out that while the general narrative is weak, ‘sequences’ such as the chase scene through the Parisian subway are ‘unprecedented’ and ‘truly modern’. Many of these defining characteristics could be attributed to the New Hollywood film form that became established after the disintegration of the PCA (Production Code Administration). The once strict norms filmmakers adhered to for the representation of violence came tumbling down, leading to spectacular acts of physical or vehicular mayhem to become an increasing selling point in popular American cinema.

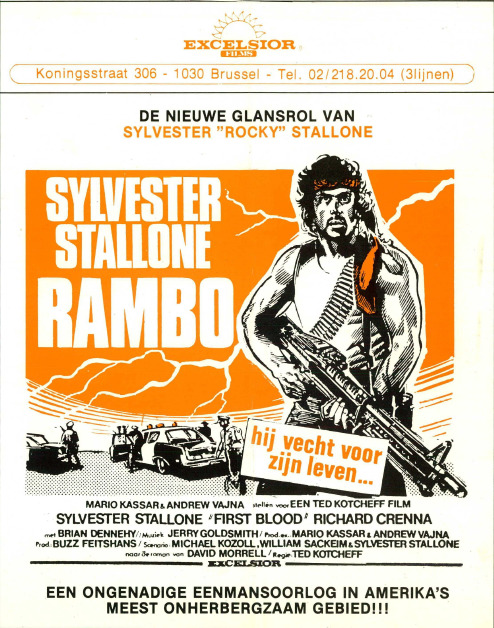

While Belgian reviewers did not quite know how to define or what to make of this new brand of violent thrill rides, one thing was certain: it was action-packed. In the next few years, reviewers competed with their own distinct way of categorisation. Most interestingly, some reviewers ignored the setting and characters in their classification altogether and treated these films as simply the latest edition in a long line of American Westerns. The review of Het Belang van Limburg described Dirty Harry as a nightly modern-day Western movie. The film’s titular hero was perceived as a descendant of the cowboys that have dominated Hollywood cinema for the last three decades. This would be the start of an enduring thematic connection, since Belgian reviewers would often link back to the Western to describe the generic specificity of films such as Death Wish (1974) and Rambo: First Blood (1982).

A Cinema of Action

When action sequences were getting more and more established in the late 1970s, films were starting to get labelled according to the type of action they featured. Films as Enter the Dragon (1973) were termed ‘Kung-Fu films’ and The Driver (1978) was dubbed a ‘chase film’, or ‘car-crash film’. In the rare case that reviewers were referring to action films, it is clear the term is referring to something else entirely than its current meaning. While it is now a label for a specific genre in which muscular heroes violently dispose of a series of villains in an urban or geopolitical setting, the term was used in the 1970s to denote a diverse set of films that prevalently featured violent action sequences – a cinema of action as it were.

By today’s account films like Coogan’s Bluff (1968) and Straw Dogs (1971) would not be anyone’s idea of an action film, yet Belgian reviewers did use these titles as examples of what they considered a new tendency of action films taking the Belgian markets by storm. Needless to say, the term action film was in this specific context mostly wielded as a derogative term that meant to belittle and problematise the New Hollywood bloodshed that splattered on the silver screen.

It wasn’t until the 1980s, when the promotional discourse of American film studios started to change, that the term action film began resembling its current meaning. As genre scholar Eric Lichtenfeld states, from the late 1970s onwards filmmakers were driven by the success of action-packed blockbuster such as Jaws (1975) and Star Wars (1977) to increasingly emphasise spectacular action as a film’s selling point. With the tentpole blockbuster evolving into a model that guided filmmakers and sales agents alike, promotional teams needed to work hard to clear these films of any association to their B-film counterpart. In an attempt to sell the grade A action film to a wider audience, producers needed a term that stressed the equally high degree of entertainment and values. Together with the much older term ‘spectacle film’ that referred to epic productions of Hollywood’s Golden Age, such as Ben-Hur (1959), ‘action film’ was appropriated and incorporated in the promotional framework of some of the genre’s most canonical iterations of the 1980s.

Belgian reviewers and its classification boards quickly picked up the new promotional discourse that coincided with these industrial changes and ‘the action film’ as a generic category became more firmly established. Films such as Rambo (1985), The Terminator (1984), and Commando (1985) are for the majority referred to as either action films, spectacle films, or action-spectacle films. The Dutch newspaper NRC Handelsblad even went so far as to call Rambo: First Blood: Part II a ‘pure action film’. Interestingly enough, this discursive shift coincided with a higher emphasis on the quality of their distinct (action)sequences rather than their story, themes and performances. De Standaard even laments the lack of an interesting action sequence at Nighthawks’ finale, demonstrating that new generic expectations were in process of being shaped.

From cheap thrills to the ultimate spectator experience

At the same time models of film exhibition started changing in Belgium. Throughout the 1970s the action film enjoyed a complex pattern of exhibition in which their releases was not connected to one particular type of venue. Much anticipated films such as Dirty Harry or The French Connection played in popular and prestigious cinemas alike, and generally got picked up in Majestic, Vooruit, Empire, Vendôme or Century for their premiere. Even arthouse cinemas such as the Ghent-based Studio Skoop weren’t shy to screen these films. By focusing on ‘author’s cinema’, filmmakers such as Sam Peckinpah and William Friedkin were already a steadfast part of the programming, and continued to be so when their work started becoming affiliated to the action film genre.

Smaller, low-budget productions and cult-films, such as the exploitative Cannon productions, or uninspired sequels, such as Death Wish II (1982), found their venue in popular city theatres Astra and Cinema Sinjoor, alongside farcical comedies and soft core pornography. Of particular importance here was Antwerp-based distribution company Excelsior Films. Throughout the 1970s and early 80s this distribution group catered a diverse set of demands and screens. In contrast to other major distributors of the time CIC and Warner/Columbia, Excelsior committed to the distribution of low-budget action films, thus contributing to the further proliferation of the action film. Among these titles were B-film that hoped to quickly capitalise on the public demand for cheap thrills and entertaining action, such as 10 to Midnight (1983) and Delta Force (1986), as well as more prestigious titles that would soon prove canonical for the genre – The Terminator (1978) and Robocop (1987) being some of the most lucrative examples. Excelsior also wasn’t shy to set up special events for its Rex cinema group. Together with distribution company NV Filimpex they got Canadian director Ted Kotcheff to Belgium to introduce his First Blood (1981).

This diversity in exhibition would cease to exist with the introduction of the megaplexes of the Kinepolis group at the end of the 80s. The infrastructural superiority of these cinemas (sound quality, screen size) and their event-style launch (red carpets, interviews, …) were attuned to make the action film into the ultimate spectator experience. In the following years, the action genre would become the staple of blockbuster Hollywood cinema, with increasingly higher budgets and larger attendance numbers. Evidently, this would result into an increasing market dominance of the Kinepolis Group whose stranglehold particularly tightened over Rex Antwerp and other cinemas that previously specialised in popular action outings. That Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991) received its avant-premiere in Kinepolis Brussels can therefore be read as something of a symbolic marker signifying changing distribution and exhibition tendencies. In light of this competition, Excelsior Films would have increasing difficulties to clear new titles and eventually disband its activities in 1993.

Moral panics and military pornography

One final component that should be discussed in relation to the action film’s introduction to the Belgian markets is the controversies and moral panic these films were often met with. Since the first action films saw itself released reviewers warned for the effects that such violent images would have on the population. This concern could take the shape of an artistic panic, in which reviewers considered this turn to the spectacular as a ‘degeneration’ to programs only interested in showcasing ‘weaponry and fighting skills’. Most often the concerns raised related to a form of societal responsibility these films seemed to ignore by making violence into a popular commodity. The violent content of the action films, and other New Hollywood titles, was read as potentially harmful to people’s understanding of violence, as well as problematic in its own right.

The most intense of these controversies dealt with specific social issues, such as youth criminality, police violence, and civil unrest. In a broader piece related to the release of Deathwish (1974), De Gazet Van Antwerpen voiced its concern on the trend of vigilante films. Fearing that people would lose their trust or take matters into their own hands, they attempted to moralize potential audience to not take these films seriously. The release of The Warriors (1979) in particular was met with moral indignation, since the film was banned in several other European countries and allegedly responsible for inciting vandalism in its US release. De Morgen wrote of the risk of copy-cat behaviour and deemed the film ‘dangerous for the young’. Adding to the topicality of these issues are film magazines Film & Televisie and Kunst & Cultuur, which occasionally published wider editorials in which the role of these violent representations was critically questioned.

Whereas similar debates were being held in the US at the time, the Belgian discourse differentiates itself by involving attitudes of anti-Americanism and anti-imperialism. In the right-wing Pallieterke, violence is framed as a distinctively American problem. It is Hollywood cinema which is unruly and aggressive, and brings its problems across Belgium borders as one reviewer states. With the Reagan years this discourse only intensified as many reviewers read the ideological agendas of the action film as downright propagandistic. Here the appreciation for the technical quality of the action film, toppled into a clear disgust for the imperialistic politics the genre represented. An arguable apotheosis of these sentiments came with Rambo: First Blood: Part II, which De Standaard simply referred to as ‘war pornography’. It’s therefore no surprise that most of these films did not receive a KT label, or were subjected to heavy edits.

That these critical discourses have mostly waned says something of how much we have taken the action film for granted. Starting out as an artistic oddity and slowly digressing into a prized commodity, the action film is now something entirely cemented in Belgium markets. That in the last decade Belgium has been investing in its own brand of action cinema with titles such as De Premier (2016), Patser (2019), and Torpedo (2019), should therefore not be read as an act of resistance to American dominance, but rather as a sign of acceptance to this distinctively American mode of filmmaking. By increasingly adapting into the very product that they set out to fight, Belgian filmmakers seem to have taken cues from Rambo’s iconic words: “to survive a war, you gotta become a war”.

Further Research

There is much more to discover about the American influence in Belgian cinema culture. Some interesting topics for further research are:

- Which moral panics did the action film generate in context of debates around terrorism, police violence, and geopolitical conflict?

- What was the promotional discourse of the first action blockbusters in Belgium like?

- How did the advent of the megaplex redrew the Belgian cinema landscape?

- How did action films circulate in Belgium from the 1990s on?

- What were the screening venues in Belgium for cult films, video nasties, and violent exploitation cinema?

Other Sources and Data

Researchers who are interested in the popularity of the American action film genre can also look at:

- Arroyo, J. (Ed.). (2000). Action/spectacle cinema: a sight and sound reader. London: British Film Institute.

- Kendrick, J. (Ed.). (2019). A Companion to the Action Film. Wiley Blackwell.

- Soberon, L. (2018). Kwaad in vele vormen: een kwantitatieve inhoudsanalyse van vijandbeelden in de Amerikaanse actiefilm. Tijdschrift voor Communicatiewetenschap, 46(4), 336-354.

- Tasker, Y. (2015). The Hollywood action and adventure film. John Wiley & Sons.

Further Reading

Quotes and sources used in this narratve:

- Biltereyst, D. (2020). Verboden Beelden. De verborgen geschiedenis van filmcensuur in België. Houtekiet.

- Lichtenfeld, E. (2007). Action speaks louder: Violence, spectacle, and the American action movie. Wesleyan University Press.

Author

Lennart Soberon is a post-doctoral researcher at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB) and artistic coordinator of non-profit arthouse KASKcinema, Ghent (BE).