Dissimilar Neighbours: Comparing Cinemagoing in Belgium and the Netherlands

Even if Belgium and the Netherlands are neighbours with closely intertwined histories, their cinema cultures are widely divergent. While a trip to the cinema was a regular outing for many Belgians, the Netherlands counted far less cinema venues and lower numbers of attendance. Structured data on cinemagoing that is available for both countries can help us explain this striking difference.

By Thunnis van Oort and Julia Noordegraaf

The Low Countries: So Alike …

Belgium and the Netherlands provide a remarkable case for an international historical comparison of the culture and economics of cinemagoing. Since Belgium and the Netherlands became separate states in 1830, the histories of the both nations have remained intertwined. The neighbouring countries, and particularly Belgium’s Dutch-speaking region of Flanders, share many similarities as relatively small, constitutional monarchies with open economies, situated in strategic positions in Western Europe.

Even if the industrialisation of Belgium took off much earlier than the late economic modernisation of the Netherlands, these differences in tempo evened out over the course of the twentieth century. From a European comparative perspective, both countries developed towards a very similar corporatist organisation of society. A process called ‘pillarisation’ created an intermediate layer between state, society, and religion, structured vertically in ideological groups. Catholics, Socialists, Liberals, Protestants (in the Netherlands), and, to some extent, the Flemish-nationalists each formed their own separate ‘pillar’ of organizations.

… but Such Divergent Cinema Cultures

Despite the many resemblances between Belgium and the Netherlands, the cinema cultures of these nations could hardly be more dissimilar. Throughout most of the twentieth century, Belgium belonged to the nations with the highest number of cinema screens and seats per capita in Europe, with very high cinema attendance rates as well. The Netherlands, in contrast, were among the lowest ranking European states in this respect.

When Belgium reached its all-time highest number of 1585 cinemas in 1957, the Netherlands only counted 531, reaching a maximum number of no more than 565 cinemas in 1961. In 1960, when the Netherlands counted 11.4 million inhabitants and Belgium 9.1 million (approximately a 4:5 ratio), the average Dutch inhabitant visited the cinema less than five times a year, while the Belgian almost went twice as often.

How can we explain the remarkable difference between these neighbouring cinema cultures? Even if no definitive answers are available, several arguments have been made to explain this disparity, using a variety of methods and perspectives: political, economic, and cultural points of view.

The Belgian Boon

Why was Belgian film culture so well-developed compared to other countries on the European continent? Several causes have been suggested. Since the nineteenth century, the market for commercial entertainment had been flourishing in Belgium well before the arrival of cinema. The fruitful convergence of the nascent cinema and the brewery and café industries yielded the successful formula of the ‘café-ciné’. Later, when the American studios dominated the global markets after World War I, the Americans considered the Belgian market attractively liberal, without import restrictions that were common in other European countries.

Although import restrictions were no obstacle either in the Netherlands during the interwar years, the strong organisation of the industry in the Netherlands made the market decidedly less free from an American perspective. Furthermore, Belgium offered a favourable fiscal climate and lacked mandatory censorship for adult audiences. There was also no local production to speak of that could compete with foreign import, though the same would apply to the Netherlands.

In Belgium, the new medium of cinema was integrated into the pillarised system, which can be interpreted as a sign that cinemagoing reached a stronger social acceptance there than in the Netherlands; a sizable network of Catholic and Socialist cinemas appeared early on. The pillarised cinema circuit grew into a formidable factor in terms of the number of cinemas and seats per capita. In oral history testimonies by former audience members, Catholic cinemas, which formed the largest portion of the pillarised circuit, were often remembered as inferior in quality to ‘real’ cinemas. Notwithstanding, they clearly competed with regular exhibitors.

The Dutch Lag

From the introduction of cinema in the late nineteenth century onwards, the Netherlands had never truly become a cinemagoing nation. A classic explanation points to the unfavourable influence of Calvinism on visual culture and outdoor entertainment in general, and film viewing in particular. Jaap Boter and Clara Pafort-Overduin have partly substantiated this classic hypothesis, using quantitative methods to demonstrate that the most orthodox Protestant areas indeed had significantly less cinemas, even if their analysis provided no evidence that different types of films were programmed in those areas.

Others have argued that cinema failed to integrate into the dominant pillarised organisation of society, in contrast to other media such as radio and newspapers that were successfully co-opted by the different pillars. While they were certainly established, Catholic or Socialist cinema circuits in the Netherlands did not reach a prominence that could seriously compete with the regular exhibition circuit.

The Dutch government appears to have weakened the demand for film through high taxes, strict censorship, and a negative discourse that discouraged cinemagoing. In response to the hostile stance of authorities, the film exhibition industry organised itself in a strong cartel. They countered the restricted demand for film by regulating the supply side, keeping prices high. This cartel was institutionalised in the form of the Nederlandse Bioscoopbond ('Netherlands Cinema Alliance', hereafter NBB), established in 1921. The very strong, centralised organisation of the Dutch industry, where distributors and exhibitors shared power, is another striking difference with the much more loosely organised Belgian industry, which was more fragmented and mostly dominated by a powerful lobby of distributors.

Comparing Cities

When we shift from the national to the city level, we can study the differences between Belgian and Dutch cinema culture in more detail. In a joint essay, Guido Convents and Karel Dibbets compared the early cinema cultures of Brussels and Amsterdam. To explain the ‘different worlds’ that existed in the two cities at the time of the emergence of the cinema, the authors point to various factors.

One of these is the flourishing urban culture in late nineteenth-century Belgium, where mass entertainment and modern forms of consumerism transformed the city into a spectacle, a notion that hardly existed in the reserved bookkeeper’s mentality that dominated the Dutch city administrations, and that impeded the development of the cinema industry through regulation that was stricter than in Brussels. Where the sale of alcohol in cinemas was for instance restricted in Amsterdam, this was not the case in Brussels.

The Cinema Belgica and Cinema Context databases provide us with information on cinemas in both cities that includes addresses, seat capacity, and opening and closing years. This allows us to analyse how patterns in the spatial location of movie theatres changed over time, in relation to wider demographic transformations.

Mapping Cinemas

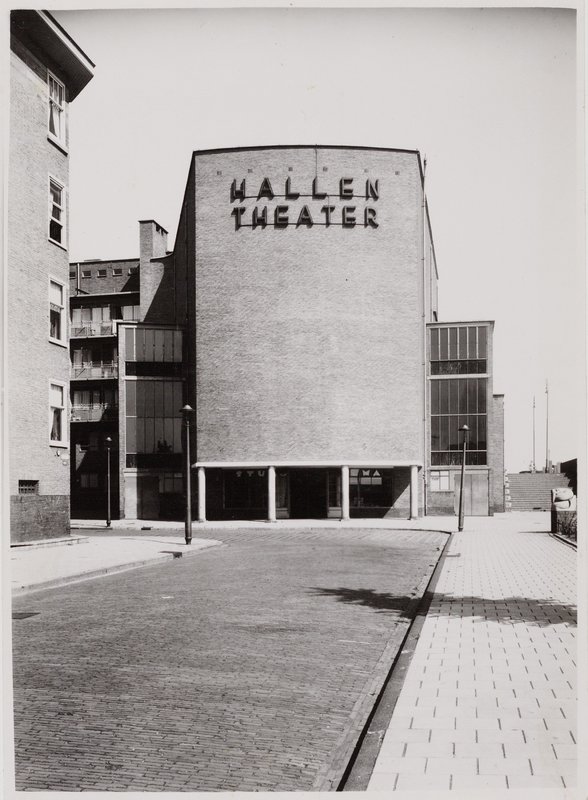

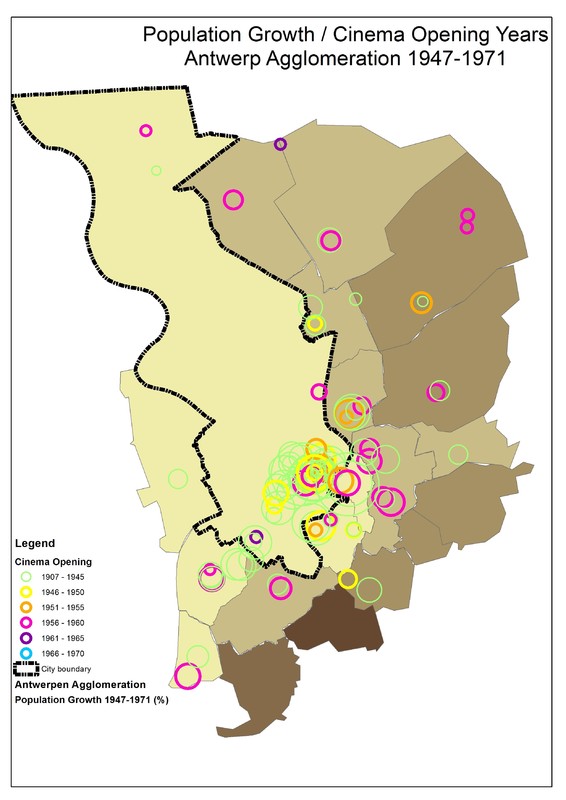

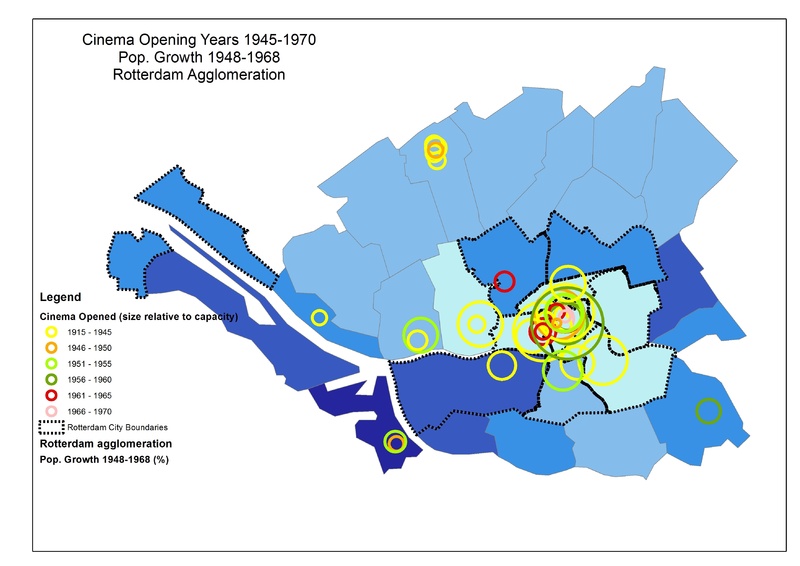

If we compare the locations of cinemas in Antwerp and Rotterdam in the postwar period, there is, first of all, a striking quantitative difference. The city of Antwerp boasted a much higher number of cinemas that were also spread wider across the agglomeration, whereas Rotterdam counted a much lower number of cinemas, more firmly concentrated in the city centre. Even if both cities went through similar processes of suburbanisation and a steep decrease in movie attendance following the heydays of the 1950s, the patterns of cinema locations differed, with the Antwerp exhibition sector responding much more dynamically to urban changes compared to a more static situation in Rotterdam.

This can be observed in more detail in the maps to the right. First of all, the difference in volume is obvious: Antwerp had far more cinemas than Rotterdam and they spread wider into the agglomeration of municipalities surrounding the city. Furthermore, during the wave of suburbanisation that continued after the war in both cities (represented on the map by the darker hues for higher population growth in the outer ring and lighter hues that signify the steady depopulation of the centre), new cinemas did open in the Antwerp agglomeration during the 1950s, while in Rotterdam hardly any new cinemas opened in the periphery.

In other words: in Antwerp, the cinemas dynamically followed the people to their suburbs, allowing audiences to visit the neighbourhood cinema around the corner, whereas in suburban Rotterdam, for many inhabitants the cinema remained a service that required a trip to the city.

This difference neatly crystallises the notable divergence in the meaning of cinema in the everyday life of the neighbouring countries: it appears that for an average Belgian a trip to the cinema was more deeply embedded into the rituals of daily life, whereas for many Dutch people, the cinema remained more of a special outing that was not as strongly integrated into the fabric of the quotidian.

Further Research

The growing availability of databases such as Cinema Belgica, Cinema Context, and the European Cinema Audiences (which provides cinema-related data on seven European cities during the 1950s) opens the way for transnational comparative research: can we explain differences between national (or local/regional) film cultures using quantitative methods? Two examples:

- Both Belgium and the Netherlands are relatively marginal film production countries compared to European countries with more robust production traditions such as France, the UK, Italy, or Sweden. What was the position of domestic film in both countries compared to the rest of the programming on offer? With Dutch and Belgian industries producing no more than 73 and 65 films respectively in the period 1950-1970, which national products did these audiences prefer?

- Cinema attendance boomed during the Second World War in the USA as well as in Europe, including in German-occupied countries. Even though there were many restrictions, film exhibitors and filmgoers still had some agency. How were German films performing at the box office in the occupied countries of Belgium and the Netherlands? To which extent did it become acceptable or even fashionable to watch German films, with their connotations of cultural imperialism?

Other Sources and Data

- Cinema Context: database containing a wealth of information on the history of cinemagoing in the Netherlands, including films, cinemas, people, and companies.

- European Cinema Audiences: database with cinema-related data and materials on seven European cities during the 1950s.

- EYE Film Institute, Dutch film database: database for Dutch cinema, currently containing information on early cinema (1900-1930), experimental films, and Dutch feature films until 1975.

- Statistics Netherlands, ‘Bioscoop- en filmhuisbezoek’: Dutch central office for statistics, offering data, including about cinema attendance.

- FOD Economie, ‘Exploitatie van de bioscoopzalen’: data on the exploitation of cinema venues in Belgium.

- Cultuurindex: Film (Boekmanstichting): data on film and cinemagoing in the Netherlands, 2005-2017.

- Dutch cinema trade press: website containing digitized documents of the Dutch trade press.

- Eurostat (2003). Cinema, TV and Radio in the EU, Data 1980–2002. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: publication providing a statistical overview on the audiovisual sector in the EU based on the statistical work carried out at Eurostat.

Further Reading

Sources used in this narrative:

- Biltereyst, D., Meers, Ph., Lotze, K., & Van de Vijver, L. (2012). Negotiating cinema’s modernity: Strategies of control and audience experiences of cinema in Belgium, 1930s-1960s. In D. Biltereyst, R. Maltby, & Ph. Meers (Eds.), Cinema, audiences and modernity: New perspectives on European cinema history (pp. 186-201). Routledge.

- Boter, J., & Pafort-Overduin, C. (2009). Compartmentalisation and its influence on film distribution and exhibition in the Netherlands, 1934-1936. In M. Ross, M. Grauer, & B. Freisleben (Eds.), Digital tools in media studies (pp. 55-68). transcript Verlag.

- Convents, G., & Dibbets, K. (2001). Verschiedene Welten: Kinokultur in Brüssel und Amsterdam. Die alte Stadt, 28(3), 240-246.

- Dibbets, K. (2006). Neutraal in een verzuild land: Het taboe van de Nederlandse filmcultuur. Tijdschrift voor Mediageschiedenis, 9(2), 46-64.

- Sedgwick, J., Pafort-Overduin, C., & Boter, J. (2012). Explanations for the restrained development of the Dutch cinema market in the 1930s. Enterprise & Society, 13(3), 634-671.

For more on the comparison between cinemagoing in the Netherlands and Belgium:

- Biltereyst, D., & van Oort, T. (2011). Censuurmodaliteiten, disciplineringspraktijken en film. Een comparatieve analyse van de historische receptie van Sergej Eisensteins Pantserkruiser Potemkin (1925) in België en Nederland. Tijdschrift voor sociale en economische geschiedenis, 8(1), 53–82.

- Biltereyst, D., van Oort, T., & Meers, Ph. (2019). Comparing historical cinema cultures: Reflections on new cinema history and comparison with a cross-national case study on Antwerp and Rotterdam. In D. Biltereyst, R. Maltby & Ph. Meers (Eds.), The Routledge companion to new cinema history (pp. 96-111). Routledge.

- Pafort-Overduin, C., Lotze, K., Jernudd, A., & van Oort, T. (in press). Moving films: Visualising film flow in three European cities in 1952. Journal for Media History.

- van Oort, T. (2017). Industrial organization of film exhibitors in the Low Countries: Comparing the Netherlands and Belgium, 1945–1960. Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, 37(3), 475–98.

- van Oort, T. et. al. (in press). Mapping film programming across post-war Europe (1952). Research Data Journal for the Humanities and Social Sciences.

Authors

Thunnis van Oort is a media historian, coordinating the Performing Arts programme line at the CREATE digital humanities project at the University of Amsterdam and is editor of the Cinema Context database. Julia Noordegraaf is professor of Digital Heritage in the department of Media Studies at the University of Amsterdam and programme leader of the CREATE project, as well as Editor-in-Chief of the Cinema Context database.