How Hollywood Conquered Belgium after the First World War

In the years following the First World War, Hollywood developed an impressive strategy to conquer the world. How did the tiny kingdom of Belgium fit into this global puzzle? A story about effective distribution, diplomatic backing, appealing pictures, and lots of money.

By Daniël Biltereyst

The Founding Myth

One of the biggest questions in cinema history is how a handful of Hollywood producers were able to control the international flow of motion pictures. How could this happen? Were Hollywood movies simply better or more attractive? How does Hollywood still dominate European screens, even though the Old Continent produces more pictures than the USA?

To get to the bottom of this question, we need to go back to the First World War and beyond the old binary of Hollywood versus Europe. The German film historian Thomas Elsaesser once called this dichotomy the founding myth of academic film studies. In reality, Hollywood was actually full of European directors, writers, and stars, while audiences often preferred Hollywood pictures over European ones.

Another important film historian, Richard Maltby, observed that little is known about what he considers to be the key to understand Hollywood’s hegemony: film distribution. By now, we know quite well what happened in major European countries like Britain, France, or Germany, where governments and the local industry at times tried to block American pictures.

But what about smaller markets with no substantial production of their own? What were the Hollywood studios’ distribution strategies there? Was the market in a country like Belgium big enough to establish a local branch?

'They seem to spring up in the night'

The Belgian case, which remains largely unexplored, is particularly well-suited to understand how Hollywood operated after the First World War. American film trade journals and official government reports tended to underline Belgium’s unique position. The Belgian market was of course small and rather complex, given its multilingual character and cultural diversity. But trade press reports praised the vitality of Belgium’s film exhibition scene.

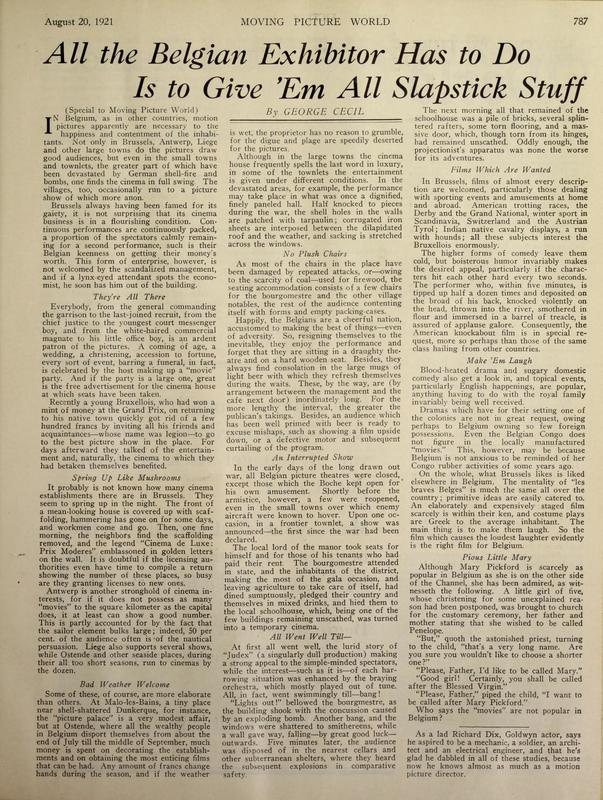

In August 1921, for example, The Moving Picture World published a juicy country report on the small kingdom. The trade journal’s correspondent wrote that in Brussels and Antwerp cinemas 'seem to spring up in the night', and added that 'it is doubtful that licensing authorities even have the time to compile a return showing the number of these places, so busy are they granting licenses to new ones'. Continuous film performances were fully packed, and exhibitors were incessantly demanding popular films, especially American comedies and slapsticks.

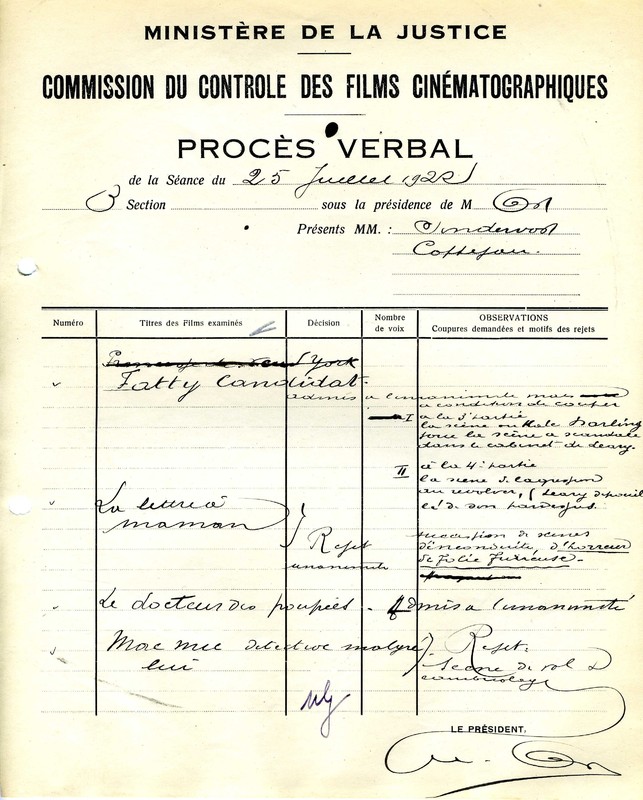

American trade journals presented Belgium not only as a vibrant film market with proportionally high numbers of screens, theaters, and film attendance. They also presented the country as a unique free trade market with an amazingly liberal film policy. Because there was no substantial local film production, the country didn’t have any form of protective policies. In contrast to most other markets, there was also no obligatory censorship. And the country’s multilingual character made it a perfect playground to test Hollywood pictures abroad.

A French Colony?

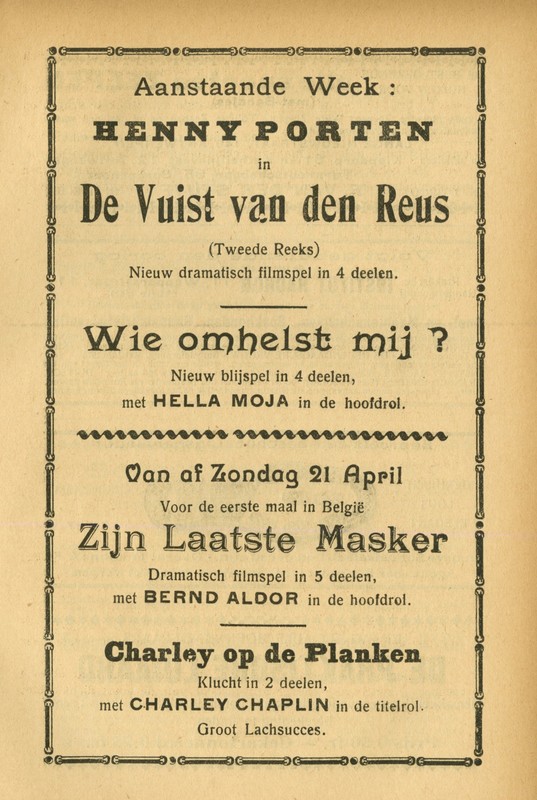

Thanks to the recent digitization of movie magazines and trade journals, such as those on the Media History Digital Library, it is now relatively easy to trace the attempts of American movie businessmen to conquer the Belgian market. One challenging factor was that French films and companies were trying to regain Belgium as if it were part of the French market, like it used to be before the war.

French companies, so a report of the American Department of Commerce stated in February 1920, often purchased Hollywood films with the exclusive rights for France and Belgium. American films like those featuring Charlie Chaplin, which were scarcely seen during the Great War, now became tremendously popular.

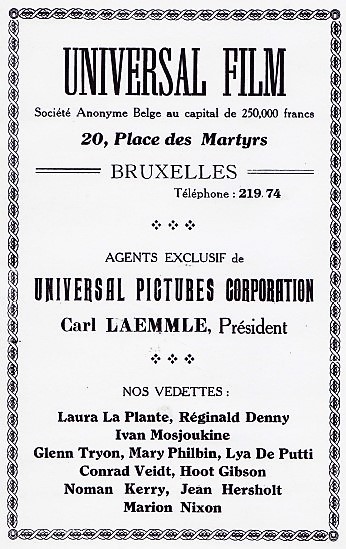

The trade press is also an incredible source to discover how Hollywood sent company representatives to negotiate territorial contracts in Europe. When the European market reopened at the end of 1918, First National, Goldwyn, and Paramount were among the few studios that began to open foreign exchanges in Europe. In 1919, most Hollywood majors had offices established across continental Europe, in some cases also in Brussels.

In the first few years after the war, many American producers operated with local distributors, or they used subsidiaries of major French companies like Gaumont or Pathé. This was the case, for instance, with Selznick Enterprise in 1920, which opened offices in Paris, Bordeaux, Lille, Lyon, Marseilles, Strasbourg, and Brussels, with Paris as its main office.

Blind Husbands, 1921

Universal’s 1919 Blind Husbands was shown as a special one-off screening on September 15, 1921, in cinema Salle de Paris in the city of Mechelen. This poster indicates that the Belgian distributor Comptoir du Film released Erich von Stroheim’s sulfurous blockbuster. Source: Stadsarchief Mechelen.

Salle de Paris, Mechelen

In the winter of 1924, another Universal picture by von Stroheim, Merry-Go-Round (1923), was shown in the same prestigious cinema, Salle de Paris. The Cinema Belgica dataset indicates that the movie was now distributed by Universal’s local branch. Source: Beeldbank Mechelen.

Towards Direct Distribution

Trade journals are only one source for investigating the distribution strategies of major American film companies. More research is needed, but the data behind Cinema Belgica clearly indicate that in the 1920s, there was a major shift towards direct distribution with local branches.

One example is Universal. Just after the war, blockbuster pictures like Blind Husbands (1919) were distributed in Belgium by French and local Belgian companies. From 1922 onwards, however, Universal applied the more lucrative model of direct distribution. Another case is Paramount, which had previously worked with the French companies Pathé and Gaumont. But in 1922, it opened a branch in Brussels.

By the end of the 1920s, when the introduction of synchronic sound film formed another major obstacle and challenge, Hollywood companies had conquered the hearts (and money) of Belgian cinephiles. Whereas in the years after the Great War, Pathé and Gaumont treated the Belgian market as a French province, things had changed drastically now. By the end of the decade, Paramount, Universal, and Fox were kingmakers in the market.

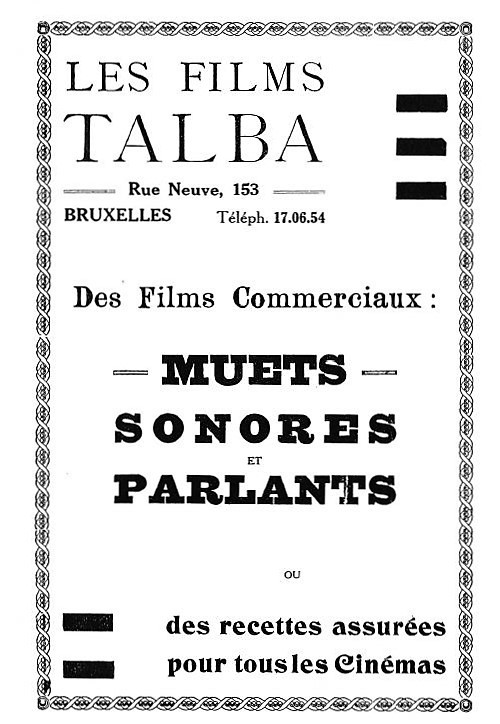

In the 1930s, they would be joined by Warner, which acquired First National in 1928 and started to release its own pictures. American distributors, however, were not the only ones to sell Hollywood fare. Many Belgian and French distributors also had American pictures on their lists, which only boosted Hollywood’s appeal.

Further Research

On Cinema Belgica there is much more to discover about Hollywood’s distribution practices and strategies. Some interesting topics for further research are:

- Were there differences in the distribution strategies of major Hollywood companies like Fox, Warner, or Paramount in Belgium?

- How big was the film catalogue of these companies?

- Did US distributors sell European movies as well?

- Given the harsh Belgian post-war resentments towards Germany, when were German films first released in Belgium, and who had these pictures in their portfolio?

- What happened with the arrival of sound? Was sound a blessing for French companies, and do we see an increase of French-language movies and French distributors on the bilingual Belgian market? What about Belgian companies? And, of course, did Hollywood lose or increase its power?

Other Sources and Data

Researchers who are interested in the topic of film distribution and the dominance of Hollywood in Belgium and Europe, can also look at:

- BelgicaPress: digitized Belgian historical newspapers of the KBR/Belgian Royal Library.

- Cinema Context: Dutch online platform with detailed information on movies’ distribution patterns in the Netherlands.

- Cine ZOOlogie: digital platform on the history of Cinema Zoologie in Antwerp, 1915-36, with online access to program booklets.

- Cinematek: library catalogue of the Royal Belgian Film Archive.

- Media History Digital Library: key platform for media and film historians with digitized film magazines and trade journals.

Further Reading

Quotes and sources used in this narrative:

- Cecil, G. (1921, August 20). All the Belgian exhibitor has to do is to give ‘em all slapstick stuff. The Moving Picture World.

- Elsaesser, T. (1994). Putting on a show: The European art movie. Sight and Sound, 4(4), 22-27.

- Maltby, R. (2020). “Perhaps everyone has forgotten just how pictures are shown to the public”: Continuous performance and double billing in the 1930s. In D. Biltereyst, R. Maltby, & Ph. Meers (Eds.), The Routledge companion to new cinema history (pp. 159-172). Routledge.

More information on the history of Belgium’s film distribution scene can be found in:

- Engelen, L. (2016). Filmdistributie in bezet België (1914-1918). Tijdschrift voor Mediageschiedenis, 19(1), 5-21.

- Vande Winkel, R. (2017). Film distribution in occupied Belgium (1940–1944): German film politics and its implementation by the ‘corporate’ organisations and the Film Guild. Tijdschrift voor Mediageschiedenis, 20(1), 46-78.

Also relevant to contextualize the Belgian case within Hollywood’s postwar strategies:

- Higson, A., & Maltby, R. (Eds.)(1999). Film Europe and film America: Cinema, commerce and cultural exchange, 1920-1939. University of Exeter Press.

- Thompson, K. (1985). Exporting entertainment: America and the world film market, 1907-1934. British Film Institute.

- Trumpbour, J. (2002). Selling Hollywood to the world: U.S. and European struggles for mastery of the global film industry, 1920-1950. Cambridge University Press.

- Ulff-Moller, J. (2001). Hollywood’s film wars with France: Film-trade diplomacy and the emergence of the French film quota policy. Rochester University Press.

Author

Daniel Biltereyst is a professor in film and media history at Ghent University and director of the Centre for Cinema and Media Studies.